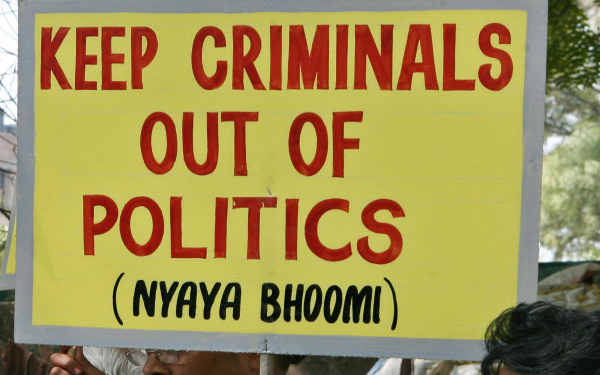

In a landmark judgment, the Supreme Court has ruled that non-disclosure of full particulars of criminal cases pending against a candidate at an election may lead to setting aside of his election. Observing that “disclosure of criminal antecedents of a candidate, especially, pertaining to heinous or serious offence or offences relating to corruption or moral turpitude at the time of filing of nomination paper as mandated by law is a categorical imperative”, and that “concealment or suppression of this nature deprives the voters to make an informed and advised choice”, a 2-judge bench of the Supreme Court comprising of Justice Dipak Misra and Justice Prafulla C. Pant held that such non-disclosure would amount to undue influence and, therefore, the election is to be declared null and void.

Dealing with the election of a President of a Panchayat in Coimbatore District in the State of Tamil Nadu, the Supreme Court was required to consider what constitutes “undue influence” in the context of Section 260 of Tamil Nadu Panchayats Act, 1994 which has adopted the similar expression as has been used under Section 123(2) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. The appellant in the case Krishnamoorthy v. Sivakumar & Ors. [Civil Appeal No. 1478 of 2015] decided by the Supreme Court on 5 February 2015, was a candidate at the said election and he was alleged to have not disclosed full particulars of the criminal cases pending against him at the time of filing his nomination form. He was elected as President of Thekampatti Panchayat, Mettupalayam Taluk, Coimbatore District in the State of Tamil Nadu in the elections held on 13.10.2006. The validity of the election was challenged on the sole ground that he had filed a false declaration suppressing the details of criminal cases pending trial against him. The Principal District Judge of Coimbatore, the Election Tribunal, came to hold that nomination papers filed by him deserved to be rejected and, therefore, he could not have contested the election, and accordingly the election was declared as null and void. The Madras High Court upheld this decision, though for certain different reasons.

On appeal, the Supreme Court upheld the decision of the High Court. The Supreme Court observed as under:

“We repeat at the cost of repetition unless a person is disqualified under law to contest the election, he cannot be disqualified to contest. But the question is when an election petition is filed before an Election Tribunal or the High Court, as the case may be, questioning the election on the ground of practising corrupt practice by the elected candidate on the foundation that he has not fully disclosed the criminal cases pending against him, as required under the Act and the Rules and the affidavit that has been filed before the Returning Officer is false and reflects total suppression, whether such a ground would be sustainable on the foundation of undue influence. We may give an example at this stage. A candidate filing his nomination paper while giving information swears an affidavit and produces before the Returning Officer stating that he has been involved in a case under Section 354 IPC and does not say anything else though cognizance has been taken or charges have been framed for the offences under Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 or offences pertaining to rape, murder, dacoity, smuggling, land grabbing, local enactments like MCOCA, U.P. Goonda Act, embezzlement, attempt to murder or any other offence which may come within the compartment of serious or heinous offences or corruption or moral turpitude. It is apt to note here that when an FIR is filed a person filling a nomination paper may not be aware of lodgement of the FIR but when cognizance is taken or charge is framed, he is definitely aware of the said situation. It is within his special knowledge. If the offences are not disclosed in entirety, the electorate remain in total darkness about such information. It can be stated with certitude that this can definitely be called antecedents for the limited purpose, that is, disclosure of information to be chosen as a representative to an elected body.”

The Supreme Court further observed as under:

“… it is luculent that free exercise of any electoral right is paramount. If there is any direct or indirect interference or attempt to interfere on the part of the candidate, it amounts to undue influence. Free exercise of the electoral right after the recent pronouncements of this Court and the amendment of the provisions are to be perceived regard being had to the purity of election and probity in public life which have their hallowedness. A voter is entitled to have an informed choice. A voter who is not satisfied with any of the candidates, as has been held in People’s Union for Civil Liberties (NOTA case), can opt not to vote for any candidate. The requirement of a disclosure, especially the criminal antecedents, enables a voter to have an informed and instructed choice. If a voter is denied of the acquaintance to the information and deprived of the condition to be apprised of the entire gamut of criminal antecedents relating to heinous or serious offences or offence of corruption or moral turpitude, the exercise of electoral right would not be an advised one. He will be exercising his franchisee with the misinformed mind. That apart, his fundamental right to know also gets nullified. The attempt has to be perceived as creating an impediment in the mind of a voter, who is expected to vote to make a free, informed and advised choice. The same is sought to be scuttled at the very commencement. It is well settled in law that election covers the entire process from the issue of the notification till the declaration of the result. … We have also culled out the principle that corrupt practice can take place prior to voting. The factum of nondisclosure of the requisite information as regards the criminal antecedents, as has been stated hereinabove is a stage prior to voting.”

Accordingly, the Supreme made the following important observations:

“While filing the nomination form, if the requisite information, as has been highlighted by us, relating to criminal antecedents, are not given, indubitably, there is an attempt to suppress, effort to misguide and keep the people in dark. This attempt undeniably and undisputedly is undue influence and, therefore, amounts to corrupt practice. It is necessary to clarify here that if a candidate gives all the particulars and despite that he secures the votes that will be an informed, advised and free exercise of right by the electorate. That is why there is a distinction between a disqualification and the corrupt practice. In an election petition, the election petitioner is required to assert about the cases in which the successful candidate is involved as per the rules and how there has been non-disclosure in the affidavit. Once that is established, it would amount to corrupt practice. We repeat at the cost of repetition, it has to be determined in an election petition by the Election Tribunal.”

Concluding a detailed 97-page judgment, the Supreme Court gave the following directions:

“(a) Disclosure of criminal antecedents of a candidate, especially, pertaining to heinous or serious offence or offences relating to corruption or moral turpitude at the time of filing of nomination paper as mandated by law is a categorical imperative.

(b) When there is non-disclosure of the offences pertaining to the areas mentioned in the preceding clause, it creates an impediment in the free exercise of electoral right.

(c) Concealment or suppression of this nature deprives the voters to make an informed and advised choice as a consequence of which it would come within the compartment of direct or indirect interference or attempt to interfere with the free exercise of the right to vote by the electorate, on the part of the candidate.

(d) As the candidate has the special knowledge of the pending cases where cognizance has been taken or charges have been framed and there is a non-disclosure on his part, it would amount to undue influence and, therefore, the election is to be declared null and void by the Election Tribunal under Section 100(1)(b) of the 1951 Act [Representation of the People Act, 1951].

(e) The question whether it materially affects the election or not will not arise in a case of this nature.”

Thus, this judgment by the Supreme Court leads to further strengthening of the election-related laws. If a candidate at an election does not disclose full particulars of the criminal cases pending against him, his election result may be set aside even if he has won such election. Thus, the candidates are required to provide full particulars of the criminal cases against him so that the voters can make an informed choice.

Full judgment of the Supreme Court can be read here.